I can’t quote a Bible verse to save my life. Not even that “Love is” one from A Walk to Remember. Still, you don’t need to know something verbatim in order for it to resonate with you.

For example, there’s a Bible verse I remember reading in the spring of 2013. I underlined it in the secondhand Dreamsicles Bible I found in the basement of a New York City church in 2007. When I first read these words, I was 23 years old. Home was a wooden bungalow without AC. My alarm clock was the barking cacophony of hostile howler monkeys who constantly reminded me I was a trespasser—a sentiment also expressed by the skunk who lived beneath the bungalow’s deck.

I lived about 40 minutes from the nearest town and I’d only have a ride (sometimes in the bed of a truck) to the store once a week. I ate pretty simplistic meals. And lots of plantain chips.

The bungalow was a simple structure. Two bedrooms, with three wooden slat walls and the fourth being a screen, separated by a barebones kitchen whose only appliance was a tabletop two-burner propane stove. There was also a bathroom; a cement floor, a real toilet, a small sink and a shower with a widow maker. At first I called it a hot water heater, but after a few electric jolts that shocked me to my core, I quickly realized it would be my cause of death on the coroner’s report. I had been to summer camp as a kid; I was capable of taking cold showers. Lord knows it was hot enough outside.

March in Nicaragua isn’t like March in the U.S. March in Nicaragua is like August in Arizona. Some nights, after shaking the scorpions out of my pillowcase, I would lay on my stiff mattress and stare up at the sorry excuse for a ceiling fan struggling to spin above me. It had one speed: a slow that was only a fraction faster than going backwards. Sometimes I was so hot I thought I was hallucinating, and the stupid fan was a mean mirage meant to punish me for my sins. So on those nights, I figured I’d read myself to sleep, and try to atone for them. Plus, what better book to put you to sleep than the Bible?

Neglected at home, where I had distractions like WiFi and people, my Dreamsicles Bible loved the attention it received in Nicaragua. It was down there, by the light of my flashlight (before it got stolen), that I first read John 21:18.

“Very truly I tell you, when you were younger you dressed yourself and went where you wanted; but when you are old you will stretch out your hands, and someone else will dress you and lead you where you do not want to go.”

If there was a light bulb in my head, it would have exploded—shooting shards of glass and tungsten filament through my skull. In 44 words, Jesus, via John, had just explained to me, via Peter, why I was in this foreign place that seemed so godforsaken at times.

Again, I was 23, a rather glorious age. Just a few months earlier, I’d had an amazing luxury apartment in New York City and an enviable job on Park Avenue; I didn’t have to be in Nicaragua—alone, isolated on a private reserve and wicked hot and itchy (thanks to pollen from those pica pica trees—aptly named because they make you pick at your skin).

Yet, here I was. Uncomfortable, but, and this is a big but, not uncertain. I knew, much like a baby sea turtle knows he needs to keep trying to get to sea despite the crashing waves pushing him backward, I was where I needed to be.

About a 10-minute jungle trek from my bungalow brought me to this beach where I got to witness the birth, and subsequent trials of these sea turtles.

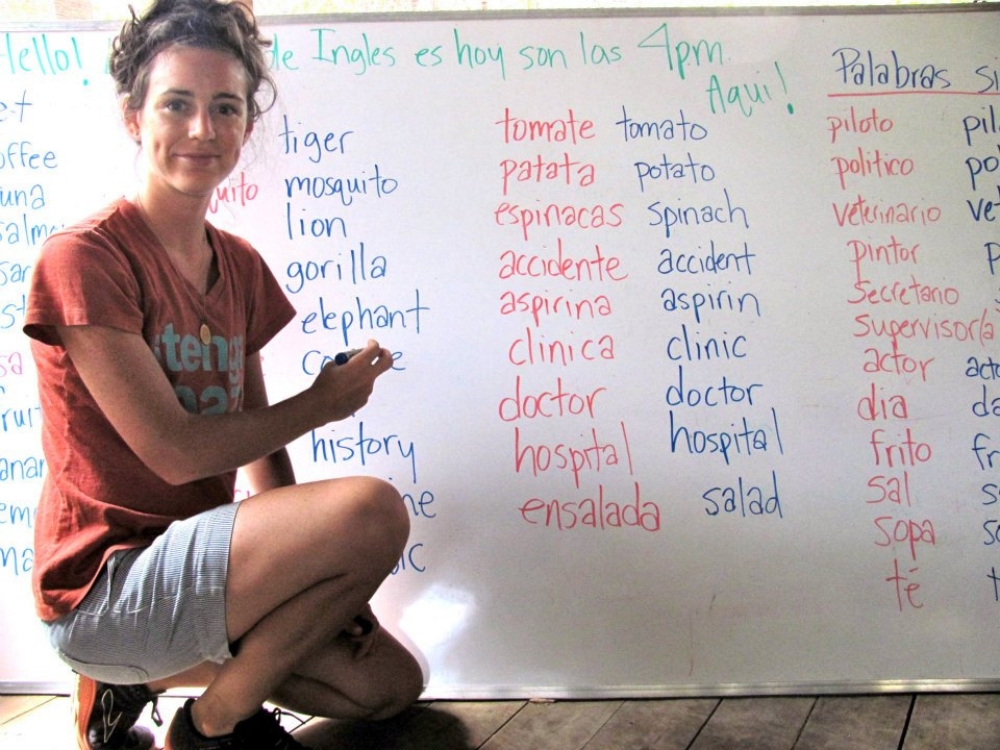

And when I forgot this was where I needed to be, I’d have 12-18 hungry brown eyes reminding me. They belonged to the brave souls, young and old, who signed up for my free English classes. Armed with little more than a white board and some markers, I got up in front of them, several times a week, and attempted to teach them something I took for granted that could be their key to catching up with the rest of the world. Without getting into the politics of Nicaragua, I will say it’s the second poorest country in the Western Hemisphere.

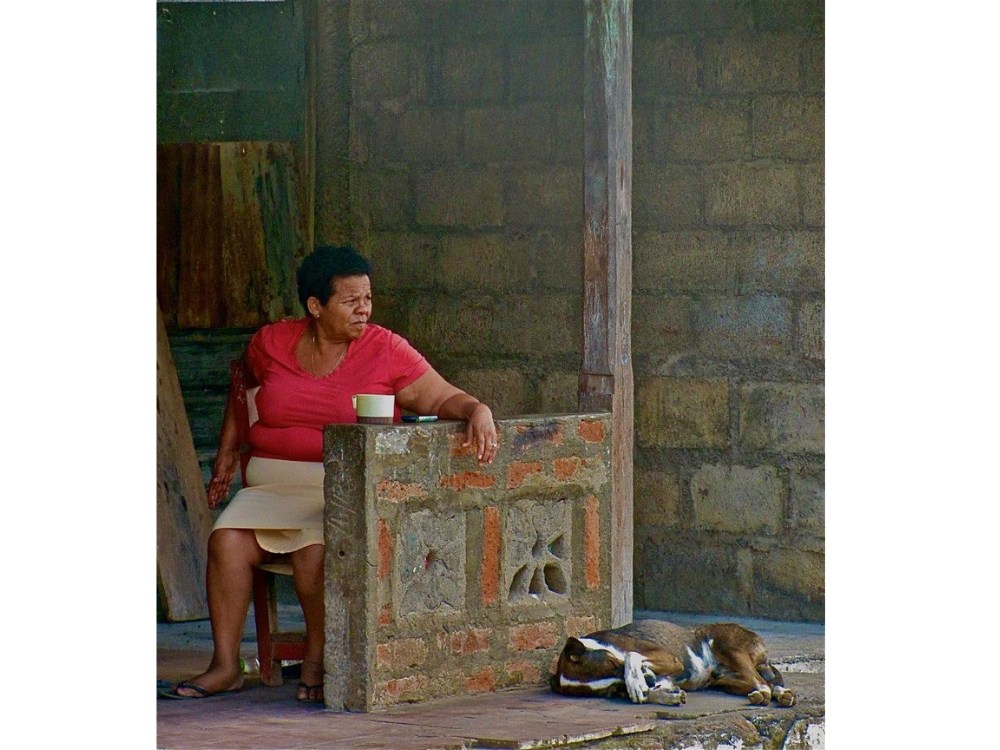

One of my favorite photos I’ve ever taken. This is the laundromat in Ometepe on Lake Nicaragua.

It was hard to remember, and pronounce, my students’ names: Zelaya, Flavio, Evert, Orling, Esperanza, etc. Zelaya had 19 brothers and sisters. He doesn’t know their names or ages, but his parents were poor and like most people in rural Nicaragua, didn’t have a TV, so they found other ways to entertain themselves.

Taken on one of the first days of class. Zelaya is on the far right end with his hand raised. Flavio has the green notebook.

Our classroom was outside, wall-less save for some sticks, but with a roof so at least we had shade. There was no AC, and I always prayed for a cross breeze. They sat on wooden benches, and I crouched in a corner. I don’t think they knew what I was saying 90% of the time, but that’s okay. I didn’t know what they were saying either. Unless Flavio was in class. His English was the best and he was my crutch, acting as translator and letting the others copy his notes when they missed a class.

I had no idea how to teach. But I faked it. I fake a lot of things.

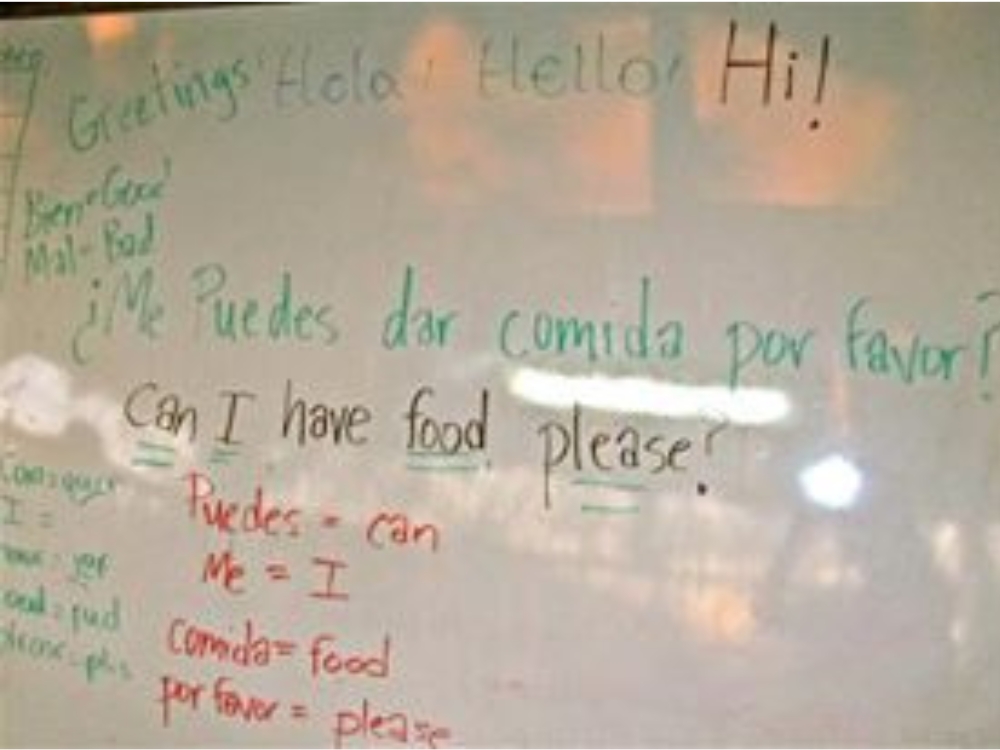

My classes didn’t follow a curriculum. Most days I would show up, spend a few minutes trying to track down a marker that worked, and then ask the students what they wanted to learn. I will never forget the laugh I let out when I asked them what they wanted to learn in our very first class. That laugh was soon followed by overwhelming sadness as I realized, it wasn’t a joke. It was a survival tactic.

They wanted me to teach them how to say “¿Me puedes dar comida por favor?” in English.

Day 1

In other words, “Can I have food please?”

If they were hungry for food, then they were ravenous for English. Most of them worked seven days a week, 12 hours a day, 28 days a month. On their days off they’d travel as far away as eight hours by bus to their hometowns where they would visit their families and bring them money. One of my youngest students, a 16-year-old named Teresa, had at least two kids. They didn’t live with her in the crowded accommodations even more rustic than mine. Sometimes I shudder to think that originally I was supposed to live in their little village.

My students didn’t work desk jobs, and I could see the physical exhaustion in their postures. Shoulders slumped, elbows on the table and heads cradled in their calloused hands, they struggled to keep their eyes open as I struggled to explain to them how to make an “H” sound. As my yoga teacher says, “It’s like the sound you make when you’re fogging up a windowpane.”

My students and I didn’t have windowpanes where we lived. If we did, maybe they would have kept the scorpions out. If they were double-paned, perhaps they would have muted the guttural growls of the howler monkeys. If you ask me, they should be called growler monkeys. I never once heard one howl.

I captured this monkey one day at sunset. On my camera. Not with my hands. I think he is waiting for his ship to come in.

It’s been three years since I wrote Flavio a goodbye letter, left it in my room (which he swept on a daily basis), and embarrassed for not lasting longer and ashamed for abandoning my students, boarded a United plane bound for the U.S. I haven’t been back to Nicaragua since. Although I came within 47 miles of the border last November when I was a guest at a five-star Marriott resort in Costa Rica. There, I spent most of my time in a bikini or in a robe at the spa. I dressed myself, and I was there on my own accord.

Where I would get my massages at El Mangroove.

Pampered, but alone, I marveled at the transparency of Costa Rica’s tranquil Bay of Papagayo. Occasionally, the boat’s captain, who didn’t speak English, would point out something interesting in the coral reef beneath us. Slowly, we trolled the glassy water. Not fishing, not snorkeling and not talking.

In the resort’s private boat, sent out for the sake of showing me around the bay, my mind was 70 miles north, reflecting on my months in Nicaragua. They were not fond memories, like the ones I was currently making in Costa Rica, but they were foundational memories. They built character in ways that only some motivational poster hanging in a military recruiter’s office can articulate.

My reverie was broken when the captain turned up the radio. I was so lost in thought I didn’t realize he was listening to music back behind the boat’s wheel. Immediately, I recognized the song. There, in the tropical midday heat, I got chills. If those words were in my Dreamsicles Bible, they’d be underlined.

And all the roads we have to walk are winding.

And all the lights that lead us there are blinding…

And sometimes, God willing, you’re called to the road that leads to where you started.