“From here on out, we’re committed.”

With those six words, my rapidly beating heart sank even further. Ben, our canyoning guide, had already spent an hour leading us through a marshy maze winding through mysterious shadows cast by high canyon walls. Hadn´t we been committed since first wading into the murky water I´d joked was the sewage runoff from Siam Water Park?

Back then I was in good spirits. Now, I was wet, spent and ready for a snack. But Ben had no intention of breaking into the waterproof bag carrying the crisps from the concessions stand at Siam Water Park and my apple. It was like we’d played our hearts out for the entire first half of the game only to be told it was just the warm-up.

I wanted to warm up. The temperature was 80 degrees 25 miles away at Tenerife´s popular beach resort, Los Christianos, home to Siam Water Park, the world´s best water park according to TripAdvisor. But here in the bottom of the Los Carrizales gorge, I was constantly curling and uncurling my wet toes to maintain blood flow. Although the four of us—Ben, myself and a couple from England—were all in wetsuits and water booties, we were as permeated as a sea of sponges.

Canyoning, in this context, meant traversing a chilly trail of spring runoff. There was never a current to worry about, but the water was often up to our necks. I thought about a book I once read where the recent jail breakees attempt to avoid leaving a trail for the cops by wading in a creek. This particular trail we were on was not visible, unless you were on it. Even then, you felt like you trespassing into a world humans had no business being in.

“I feel like we stumbled onto the set of Jurassic Park,” said Imogen, the English girl who I took an immediate liking to. Like me, she´d never been canyoning, and like me, she was willing to vocalize her fears.

We´d first bonded an hour earlier when we´d started this journey.

“Find a bush,” Ben said. Knowing it would take us 10 minutes and at least a dozen four-letter words to get our wetsuits on, he wanted to make sure we emptied our bladders in advance. Imogen and I headed in the same direction, in search of a bush suitable for squatting.

As I peed, I wondered what I´d gotten myself into. In my mind, I saw the words from Ben´s email when I’d first reached out to Canyon Tenerife a week ago.

“Los Carrizales Canyon is an aquatic canyon with slides, jumps and abseils,” he wrote. Then he went on to describe the hike back up to the car. “Steep, vertigo (sic) and quite intense.” It´s like he was trying to talk me out of it. I basically replied NBD, I’m from Montana.

Masca, the nearest “town” and our meeting place for Los Carrizales.

Photo: Trover

The last time I´d grossly underestimated the difficulty of a physical activity was when I went coasteering in Portugal in August. Now, I’ve never been to Navy Seal Hell Week, but I imagine they have a coasteering day. Even three days after completing the course—rock climbing, cliff jumping and rappelling our way along four miles of steep Atlantic coastline—I couldn´t squeeze a bottle of toothpaste without grimacing. My arms were as useless as T´Rex´s.

Canyoning, on the other hand, doesn´t require as much upper body strength. At least it didn´t in Los Carrizales where were constantly going with gravity. There was no jumping into a pool of water and climbing back up the rock walls to do it again. In that sense, canyoning was less physically demanding than coasteering. However, it more than made up for that with its increased toll on your mental state. In coasteering, I was jumping, sometimes from heights of more than 30 feet into the ocean. In canyoning, our target was far less forgiving. I.e. you had to carefully calculate where to jump to avoid colliding with rock.

“Bend your knees,” Ben would say before a jump where the water below was shallow. The canyon we´d entered, upon “committing” was now characterized by a series of sudden drop-offs. We’d walk 100 feet to the next edge, sometimes staring down at 65 feet of sheer, slick rock. Naturally, my thought process worked like this: if it´s so shallow we have to be concerned about breaking our legs, why are we jumping into it? I think Ben´s thought process worked like this: “If it looks dangerous, do it.” (And don´t forget to turn on the GoPro.)

Ben following me down an abseil.

As much as I questioned his sanity, I felt safe with Ben. He´s a certified EMT in his native France where he works on a helicopter ambulance. When we asked who he rescues, he didn’t even bother lying. “People out canyoning,” he said before going on to talk about some Japanese men whose bodies he had to retrieve when they tried to sled down a mountain. Ben´s seen more blood and bones in one season than most people see in a lifetime of Halloweens.

But Ben was a pro. When he canyoned, he came prepared. He made us carry three waterproof packs filled with supplies. Technically, we threw them down the canyon for much of our trip. I came to hate the sound of their echoes bouncing off the canyon walls.

“SPLASHhhhhhhhhhhhh!” Ben had thrown his big yellow pack down into the pool below and was now waiting for us to catch up so he could coach us on the jump, slide or abseil down. It was unspoken, but unanimous. Rob, Imogen´s cardiologist husband, would always go first. Like us, he´d never been canyoning, but unlike us, his legs didn´t shake uncontrollably. We all may have had the same amount of courage, after all, we completed the same jumps, but Rob didn´t take nearly as long to summon his.

Ben literally talking Imogen off a ledge.

“SPLASHhhhhhhhh!”

I never saw the look on Rob´s face when he hit the water. Just his helmet bobbing as he swam to the water’s edge to make room for me to jump and join him. As a seven-year-old, I didn´t hesitate to climb the ladder up to the high dive at the city pool despite hearing about how my mom had done it when she was four or five, breaking her neck or something like that in the process.

Heights have never scared me. But heights combined with enclosing rock walls and pools of sketchy depths made me wonder how they´d mark the place where my body would shatter and splatter. For car accidents it’s white wooden crosses and for cyclists, white ghost bikes. Perhaps canyoners use pictographs?

Fortunately, I did not meet my demise* in Los Carrizales Canyon. Although, in a way, parts of me perished. Don´t get me wrong, I still have a lot of “I can’ts” in me. But after every leap—feeling the shock of the cold water followed by the burning sensation of what I´d sucked up into my sinuses (it´s nearly impossible to have an impact like that and not take in water up your nose)—I realized every “I can’t” I’d told Ben as he tried to cajole me into jumping had turned into an “I did.”

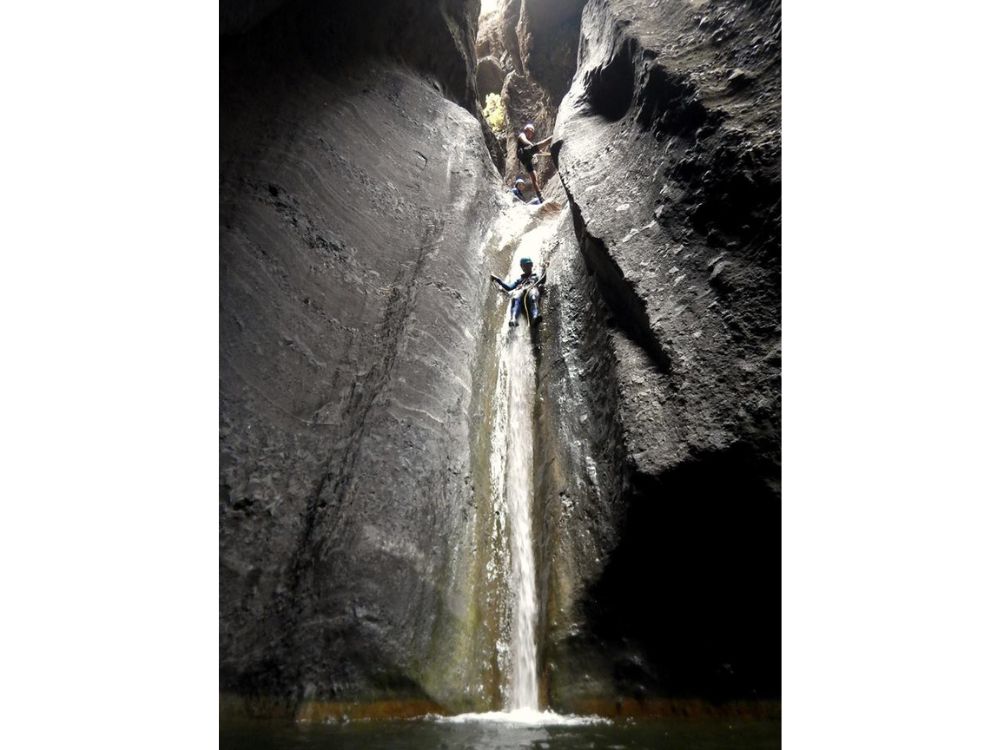

That´s not to say I was a good sport for the entire three hours of canyoning. There was at least an hour where I didn´t say anything unless it was absolutely essential. I.e. “Where do I put my left hand?” or “Oops, I undid my carabiner.” I also demanded a complete tutorial for the slide where it was essential we kept our heads pressed against the rock we slid down.

One of the slides. It’s faster than anything at Siam Water Park!

Photo: Canyon Tenerife

At this point, my feet were numb enough you could hit them with a hammer and I wouldn´t flinch. My legs were so sore they wobbled worse than the town drunk´s. I tried to turn off my thoughts, to conserve energy and to stop myself from going down the dangerous road of ruminating on things like the blood splatters on Ben´s helmet.

“I thought it was blood too,” Rob said later on when we found out it was just a spray of reddish brown paint. The only blood I saw while canyoning was the bright red pin pricks on my arms and hands. Often, to avoid slipping on the wet rocks, I reached out to grab a hold of the nearest bush, not realizing said bush was covered in thorns, or worse, a cactus.

Between the three of us, Rob, Imogen and I must have fallen at least 20 times. Our reinforced ¨Singing Rocks¨ nappie shorts over our wetsuits offered some padding in the bum area, but not enough that Imogen didn´t say, “It will be funny to see all of our bruises in the light tomorrow.”

A geologist’s wet dream.

Imogen, afraid of heights but hiding it under a semi-dark English sense of humor, always made me laugh. “It would be much easier to jump during the dark when you can´t see how high up you are,” she noted after one particularly jarring jump. “Sure,” I said, “The jumping would be easier but the landing would suck.”

“Aim for that dark green spot,” “tighten your bum and core” or “cross your arms over your chest” Ben would say when coaching us before a jump. After six years of leading five-hour tours here, he probably could navigate it at night.

My method-down of choice was always abseiling. Whereas I didn´t trust myself to jump at least two feet out, so as not to hit the rock shelf between me and the pool below, I was confident I could hold onto a piece of rope.

Me on one of the final abseils.

“Do people ever think they´re helping you out and toss the rope bag over into the next pool without realizing it´s one that requires abseiling?” Rob asked. We´d all taken turns heaving the bags ahead, 20 feet below and forward, down the canyon. But if we’d accidentally thrown the rope bag down, we´d be royally screwed.

“Yes,” Ben said cringing, “But that´s why I have two ropes and they´re in separate bags.”

Never make the mistake of tossing the rope bag while the rope is still in it.

After three hours of traversing the canyon, via water, Ben told us this would be our last jump. He didn’t need to coach me on this one. I´ve never jumped so fast in my life. I think I flew off that ledge. I just wanted to be done, dry and fed.

A few minutes later, we stripped off our wetsuits and broke into our snack bag. The crisps were crumbs so fine you could snort them, and the apple I’d painstakingly picked out at the market was brown and bruised. We ate them anyway. Ben said we’d need the energy for the hike back to the car.

The “hike” turned out to be more of a scramble along the sides of the gorge. We must have climbed a couple thousand feet, under the hot sun, surrounded by cactus, lava rock and the occasional curious lizard or mantis. My mantra became “Don´t look down.” I allowed my eyes to only look at my next step and the next handhold for my hands. Looking down at the depths below and realizing how high we were and how there was no handrail, tree line or harness preventing a fall was akin to sanity suicide.

The hiking terrain here be like…

Photo: Canyon Tenerife

Finally, after an hour and a half of “hiking”—most of it spent not talking since we were all of out breath—we were back at Ben´s red Peugeot. He took a cooler out of the car and opened it. We grabbed cold cans of Schweppes like they were winning lottery tickets and said cheers, not even taking the time to ensure eye contact.

After crushing his can, Rob went to the car to retrieve his bag. He returned carrying a pack of smokes.

“Wait a minute,” Ben said, “You´re a doctor!” He was voicing what the rest of us were thinking.

Rob lit it anyway. “I’m on holiday,” he said, taking a drag to Imogen´s horror.

I didn´t dare to judge. After completing something like canyoning, I don’t think you should be too concerned about a celebratory cigarette.

*Although I´m still not certain I have contracted a flesh eating bacteria.