Wolves are my favorite animal, but my parents see them as the enemy that kills their livestock

I have this dream: I’m six years old and shouting at my mom, but she doesn’t seem to hear me. “Don’t shoot!” I yell, but the rifle is still raised, her finger heavy on the trigger, and the wolf she’s squinting at through her scope is completely oblivious.

The animal is 150 yards away, trotting along the tree line, headed toward the cows my mom and I just fed. Short of putting myself between the wolf and the muzzle, there’s not much I can do to stop my mom. She’s only five foot two, but I’ve seen her blow the heads off several coyotes, from twice as far away, and a wolf is a much larger target.

Fortunately for me, and the wolf, I always wake up before the gun goes off.

Even at 33 years old, I still have this dream, especially when I’m visiting my childhood home just outside Lewistown, Montana. Although I now live a couple hours away, in Billings, and jet around the world for my job as a travel writer, home will always be 1,500 acres of bucolic alfalfa fields in the foothills of the Judith Mountains. Known as the Lazy JK, our ranch has been in the family for five generations. When I was a kid, we raised sheep, hogs, and Black Angus cattle, all branded with a sideways or “lazy” J on top of a sideways K. But after struggling to put food on the table for me and my two brothers, my parents, Mel and Becky, eventually took the sheep and hogs “to town.” I never saw them again, but our cattle herd doubled. In Montana, cattle are far more lucrative.

Much like you wouldn’t ask someone their salary, you’d never ask a rancher how many cows they have. Still, my folks have always known their exact number. And they’ve never been able to afford to lose a single one, to a wolf or otherwise.

Unfortunately for me, wolves have always been my favorite animal. My obsession with Canis lupus can be traced back to Little Red Riding Hood. While other four-year-olds were rooting for the naive girl bringing flowers to her sick grandmother, I was Team Wolf. For some reason that I should probably discuss with my therapist, I respected a cunning creature who killed the innocent far more than I cared about a kid my own age.

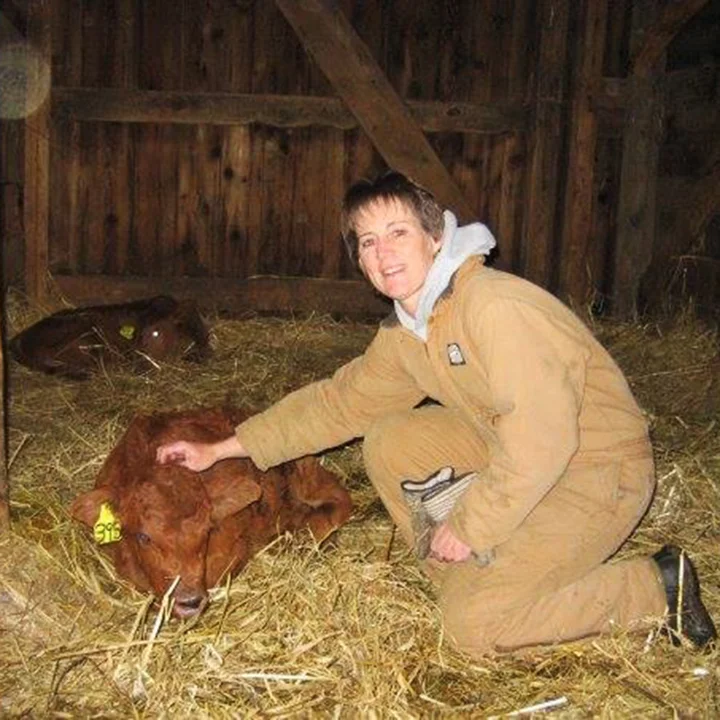

The author’s mother with two calves (Photo: Katie Jackson)

The author’s father (Photo: Katie Jackson)

There’s no better place in Montana, or perhaps the world, to see wolves in the wild than the 2.2 million acres of Yellowstone National Park. And there’s no better person to introduce you to them than 54-year-old Nathan Varley. As the founder of Yellowstone Wolf Tracker, a wildlife guiding service, he’s been helping visitors find wolves in Yellowstone since 1995, the year the animals were reintroduced to the park after a 70-year absence. I reached out to Varley in December and booked a tour for the first week of January. Then I reserved a room for us at Sage Lodge, a property just outside the park, which started partnering with Varley and other guides to offer wolf-watching packages shortly after it opened in 2021.

Montana’s economy is dominated by agriculture and ecotourism. The state is home to 2.2 million head of cattle (outnumbering residents two to one), and Yellowstone and Glacier National Park are visited by eight million people combined annually. So you can imagine that, around here, wolves are about as polarizing as pineapple on pizza. “If you want to get in a fistfight in Montana, walk into any bar and ask about wolves,” Brad Schuelke, activities manager at Sage Lodge, tells me in January when I ask if he’s seen any wolves lately.

Wolf tourism, a relatively new phenomenon, is a growing source of revenue in Montana. In 2021, Kimpton Armory Hotel Bozeman started offering a wolf-watching package. It starts at $624 and includes a one-night stay and an all-day tour in Yellowstone.

About the same time, the newly opened Sage Lodge started partnering with Varley, who charges $800 a day, and other local tour guides, to offer a wolf-watching package. It was so popular that a year later the property launched its own tours, starting at $950 for the day, led by an in-house team of guides. And last summer the Four Seasons Resort and Residences in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, announced it was adding a $16,000 wolf-watching package, which includes a private flight to Yellowstone’s North Entrance. Of course, there are also independent guides, like Yellowstone Safari Company, specializing in wolf tours. Their day trips start at $350, and for a guide, I recommend Nate Udd, a huge wolf enthusiast and talented artist.

Schuelke leads wildlife-watching tours in Yellowstone every other day, but it’s been a week and a half since he’s seen any wolves. Still, he’s hopeful. “I have a feeling you guys will get lucky tomorrow,” he says.

The author wolf-watching (Photo: Katie Jackson)

Wolf Project volunteers (Photo: Katie Jackson)

At 6:30 the next morning, my parents and I climb into a white SUV idling in the empty parking lot of the Gardiner, Montana, Chamber of Commerce. Varley looks like he’s sponsored by Mammut, and my parents are clad in head-to-toe Carhartt. My dad is even sporting the same muck boots he wears on the ranch. I’m wearing a Canada Goose Expedition jacket. The door is plastered with a giant paw-print logo with the words “Wolf Tracker” and the license plate reads “Wolves Belong.”

While at least a dozen licensed guides offer wolf-watching tours in the area, I opted for Varley because he’s a product of Yellowstone. Both of his biologist parents were rangers, and he grew up in the park. He vividly recalls the time he couldn’t play on the local playground because a bull elk had gotten its antlers stuck in a swing. The fascination stuck, and Varley, with his tall, lanky frame, thick dark hair, and round glasses, followed in his folks’ footsteps and studied biology. He got a PhD in ecology from the University of Alberta, and in 1995, he volunteered to assist with the Yellowstone Gray Wolf Recovery Project. He’s worked with wolves ever since.

After we drive through the iconic Roosevelt Arch, Yellowstone’s answer to the Arc de Triomphe, Varley starts to explain that the winding, new pavement we’re climbing is the old stagecoach road. Until last summer, it was a single-lane dirt track. With one hand on the wheel, he uses his other to point to the Yellowstone River carving out the valley below.

“The main road was down there, but this summer’s 500-year flood—or 1,000-year-flood if you’re being optimistic—destroyed several sections,” he says. The devastating flooding made international news and forced the park to evacuate visitors and close for more than a week.

Fortunately, the natural disaster didn’t negatively impact the park’s wolf population which hovers at around 100 and is spread out over eight packs. “It’s a number most experts think is sustainable,” says Varley. While the 3,472-square-mile park has been home to upward of 200 wolves at a time in previous years, it’s not big enough to support that many. If they’re ambitious enough or extra territorial, a single pack alone can claim up to 1,000 square miles. When you have too many packs in an area or too many wolves in a pack, they fight.

“If you want to get in a fistfight in Montana, walk into any bar and ask about wolves.”

Inevitably, the conversation turns to the reintroduction of wolves to Yellowstone. My dad takes the floor first. In his opinion, the reintroduction was more about prey than predator. Wolves had lived on the land that now makes up Yellowstone long before it was designated the world’s first national park in 1872. But by the mid-1900s, you were just about as likely to see a unicorn in the park as you were a wolf. The animals were viewed as a threat to more desirable species like deer and elk, so park rangers shot, trapped, and poisoned wolves until they were completely eradicated from the park. Without an effective predator, the elk population mushroomed. Between the 1930s and the 1960s, there were so many elk that rangers had to start shooting them as well.

“The Park Service was doing a poor job managing the elk,” my dad says, putting his coffee down in the car’s cup holder so he can make his point with both hands. “That’s why they needed the wolves.”

“You’re spot-on,” Varley says. “In places that don’t have hunters, you need natural culling agents, like wolves. The park figured that out.”

“What’s harder for the Park Service?” my dad asks. “Managing wildlife or managing visitors?”

“All of the NPS management is for the visitors,” Varley says. “For example, when I worked in bear management, the main question we asked was: How do we manage the people so they don’t bother the bears?”

“Yeah, you have to watch out for visitors like me,” says my mom. “I’ve been telling my coworkers I’m going on a wolf-hunting— not wolf-watching—tour.” She pauses, then delivers the punch line. “It must be a Freudian slip!”

Varley and I don’t find it very funny. But my dad laughs.

Before my dad can share one of his equally bad dad jokes, Varley’s radio cackles to life. He’s one of a lucky few with access to a confidential channel used by other guides and naturalists to share sightings.

“Great news! Looks like the Junction Butte pack is in the Lamar Valley near Dorothy’s Pullout,” says the voice on the radio.

“Copy that,” answers Varley, putting a little more pressure on the gas pedal.

The Lamar Valley sits at 6,400 feet, a relatively low elevation for Yellowstone. It’s the promised land for bison, elk, and other ungulates, especially in the winter. Why hoof it through five feet of snow to find food if you don’t have to?

The best way to locate wolves is to locate their food source, and wolves in Yellowstone primarily eat elk. Word on the radio is that the Junction Butte pack killed a bull sometime last night or early this morning on the western end of the valley.

The author and her parents at Dorothy’s Pullout (Photo: Katie Jackson)

Forty minutes later we’re at Dorothy’s Pullout, a nondescript widening in the road just past Tower Junction, which is where most people stop. “It’s not on any official park map,” says Varley. “But us guides know of it, even if most of us don’t know who Dorothy is.” I count 12 parked vehicles, many with out-of-state plates. Their occupants are all outside, bundled up against the cold. As they shuffle their feet, they keep one eye on the meadow in front of us and the other on the five or six young men and women slipping into neon orange and yellow Wolf Project vests.

“One of the best ways to find the wolves is to find the vests,” says Varley.

The people wearing the vests are employees and volunteers of the Yellowstone Wolf Project, a research initiative funded by the park’s official non-profit partner, Yellowstone Forever. Unlike Varley and other guides, the Wolf Project team has access to the collared wolves’ radio frequencies. They can pinpoint their exact locations in real time.

Although the temperature is barely in the double digits, we pile out of the comfort of the SUV. Varley hands us binoculars and starts to set up Swarovski scopes. The objects of our obsession are microscopic black dots on a barren snow-covered hillside more than a mile away. Through the high-powered optic instruments, however, each individual animal comes to life.

“Looks like there are 22 wolves,” my dad says, as if it’s a race to see who can count them. It’s a significant sighting. Most people are lucky to see one or two. I’ve been to Yellowstone half a dozen times, and I’ve never seen more than five or six at once.

As I watch my parents, I can’t tell who is more excited: my diabetic dad, who is so fixated on the wolves he forgets to check his blood sugar, or my mom, who is monopolizing the best scope. Both are animated as they rapid-fire questions at Varley. “What are they doing? Can you tell how old they are? Why are there so many?” None of their queries have to do with hunting. Here in the Lamar Valley, 200 miles away from their ranch, wolves aren’t a nuisance, they’re a novelty.

We watch the wolves for nearly two hours. Most are lying down, digesting their breakfast of freshly killed elk. At one point, it looks as though a few yearlings have mustered up the energy to chase away the fox, coyotes, and birds helping themselves to what’s left of the carcass. But eventually they spin in several circles and plop back down in the snow.

When we can no longer feel our toes, we retreat to the SUV. While the wolves nap, Varley wants to show us some golden eagles and moose that have become mainstays in the valley. Heater cranked to high, we cruise east, deeper into the park. The eagles, a mating pair who Varley estimates to be in their twenties, are perched in a nest overlooking a marshy area where two bull moose are grazing. In July we’d be jockeying for position with ten to fifteen other vehicles. Today it’s just us.

In January of 2021, Yellowstone welcomed 96,000 visitors. That July—the park’s busiest month—saw nearly 3.5 million. The year broke the park’s visitation record. As Montana residents, we know better than to come to Yellowstone in the summer. That said, we don’t know until we’re back at Dorothy’s Pullout, watching the Junction Butte pack wake up, that we’ve somehow managed to pick the best day of the entire year for wolf-watching.

Normally, planes aren’t allowed in Yellowstone’s airspace. So the Piper Super Cub performing circles overhead doesn’t go unnoticed. A wolf watcher on my left says something about a helicopter. We hear it before we see it. “I had no idea this was happening today,” says Varley, scrambling to position our spotting scopes. “But boy did we luck out.” There’s only one reason that there would be a heli in the park: they’re collaring the wolves.